Books may be purchased through the Anchorage Museum Shop or Princeton Architectural Press.

In a Coca-Cola advertisement from 1943, a group of soldiers are depicted enjoying an impromptu baseball game at a remote Alaskan military encampment. Several are shown cheerfully hoisting a Coke, rendered instantly legible by its iconically ribbed, green-glassed bottle. "From Atlanta to the Seven Seas," declares the ad text, "Coca-Cola has become the high sign between kindly minded strangers, the symbol of a friendlier way of living." Coke, the ad implied, was home in a bottle. "The pause that refreshes works as well in the Yukon as it does in Youngstown."

In the background of the ad, on the edge of the glacial baseball diamond, lay another American icon, one that was also being spread through the incidental globalization of World War II. Along with Coke, chewing gum, the Jeep, the Kilroy was Here logo, and any number of other field-deployed accoutrements of the U.S. military campaign, it, too, had become a kind of symbol for American ingenuity, can-do pluck, and ubiquitous cultural influence. There, in the ad, low-slung on the horizon, lies an instantly recognizable, arch-like and half-barreled, form: the Quonset hut.

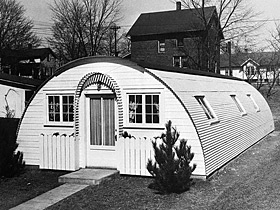

Display model of a Quonset house erected by the Great Lakes Steel Corporation in Mansfield, Ohio, 1946

Image donated by Corbis-Bettmann, BE029330

While the Quonset hut could claim any number of literal or metaphoric predecessors, ranging from the cylindrical "longhouses" of the local Narragansett tribe (in whose language, coincidentally, Quonset itself means "long place" ) to the British Army's Nissen hut, it was, in effect, a historical hybrid, melding the traditional housing forms typically adopted by nomadic peoples with the latest advances in materials and prefabrication technologies. Its lines were clean, its facade unadorned, but it spoke less about modernism than wartime contingency (which is not to say the two are unrelated), or what has been described as the "spirit of functional consequence [that] gripped every facet of wartime construction, from the steady stream of more than one hundred thousand Quonset huts made and shipped overseas to the network of coastal defenses that guarded our shores against the possibility of enemy attack."

With the Quonset, housing was a weapon. A September 1946 advertisement for Kimberly-Clark (makers of Kimsul, an insulation used in Quonsets) shows a ("recently declassified") photo of a vast collection of sleek Quonsets; the accompanying text states: "A massive Naval installation on New Guinea gives a better idea of the Quonset's contribution to the winning of the war." It was a kind of heroic icon-"A new Jeep in the military field," as a Stran-Steel ad put it, part of the same massive industrial complex that was churning out bombers and munitions. Its appearance on some Pacific Atoll represented not just an advance of troops, but a virtual outpost of America, a home away from home, a Coca-Cola of the landscape. In an age prior to McDonald's or the corporate Holiday Inn, the Quonsets, as they sprang up, arranged in miniature Instant Cities-"the world's largest housing project," as another Stran-Steel ad went-from the Aleutians to the Ardennes, promised standardization and efficiency, the soon-to-be buzzwords of the commodified American landscape. They were standard-bearers of sorts, although of exactly what it had yet to be seen. As the design historian Thomas Hine writes: "As American forces moved island by island across the Pacific, [the Seabees] proved to be the most gifted scroungers of all...There was something joyous in the surprising things they did with oil drums and Quonset huts that seemed then to open the door to industrial materials and forms used in unexpected ways."

War, despite its overwhelming air of destructiveness, is also a creative force. The very process of waging war requires, for each age, new design solutions, new products. That so many useful products and technologies are bred from war is not only a consequence of the increased expenditures for research and development in such a period-the utter massing of talent and assets towards an overarching goal of victory-but also a condition of the very lack of resources available-whether time, money, or materials. For a designer such as Charles Eames, the constraints of the war represented an opportunity: to look again at commonly accepted objects, to find new ways of doing things when previous materials and methods were unavailable. The Quonset, indeed, was created in the spirit of the Eamesian declaration-"design should bring the most of the best to the greatest number of people for the least"-to which only need be added the caveat: and do it in three months or less.

How to use retained earnings formula on a balance sheet.